TABLE OF CONTENTS

Navicular syndrome in horses

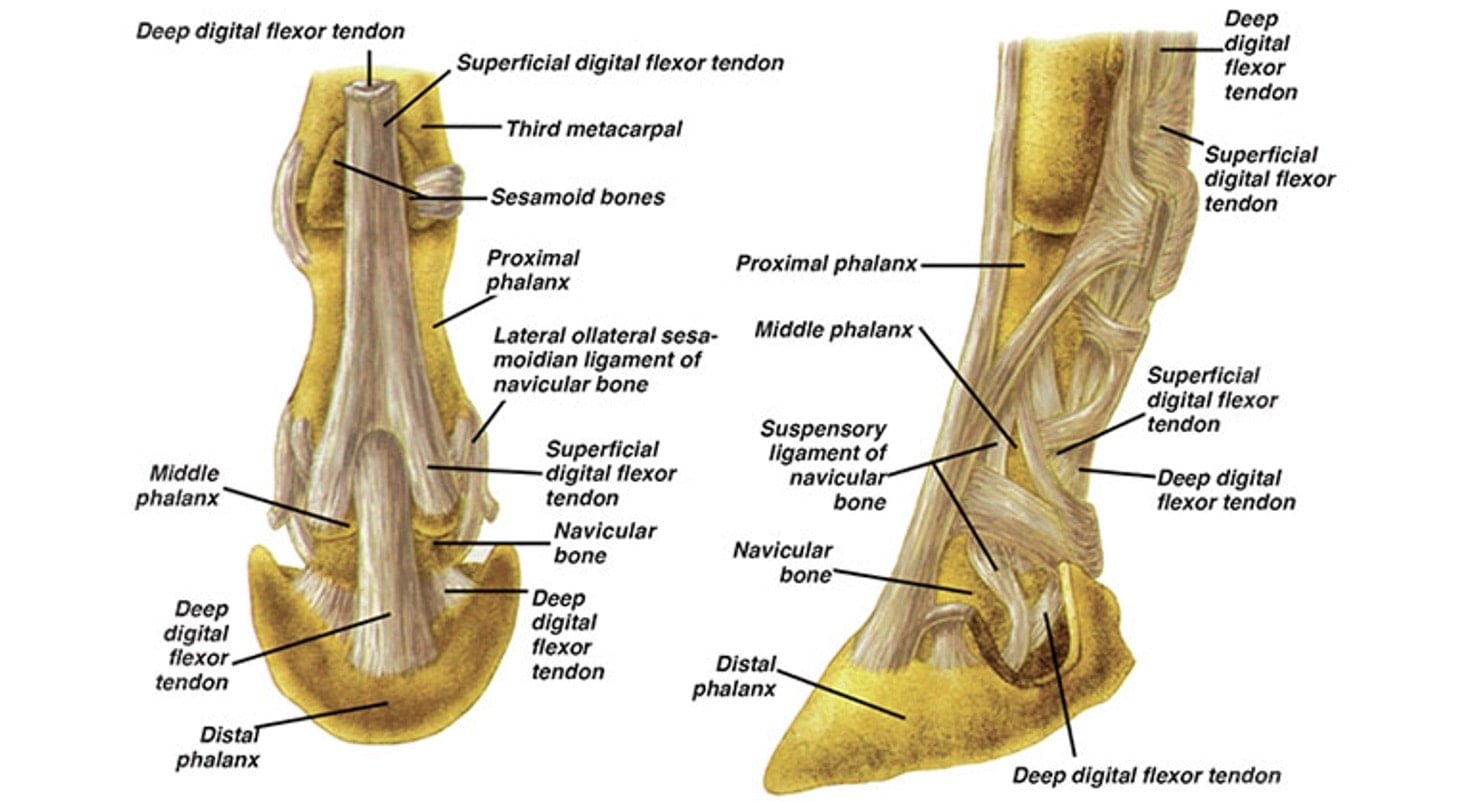

Navicular syndrome in horses often called Navicular disease, is a syndrome of soundness problems in horses. It most commonly describes an inflammation or degeneration of the navicular bone and its surrounding tissues, usually on the front feet. It can lead to significant and even disabling lameness.

Navicular disease is one of the most common causes of chronic forelimb lameness in the athletic horse but is essentially unknown in ponies and donkeys.

Navicular disease is a chronic degenerative condition of the navicular bone that involves-

- Focal loss of the medullary architecture (with subsequent synovial invagination),

- Medullary sclerosis combined with damage to the fibrocartilage on the flexor surface of the bone,

- Traumatic fibrillation of the deep digital flexor tendon from contact with the damaged flexor surface of the bone with adhesion formation between the tendon and bone, and

- Enthesiophyte formation on the proximal and distal borders of the bone.

Etiology

The pathophysiology of navicular disease is unknown. The two proposed causes of navicular disease are vascular compromise and biomechanical abnormalities leading to tissue degeneration.

With the vascular theory, thrombosis of the navicular arteries within the navicular bone, partial or complete occlusion of the digital arteries at the level of the pastern and fetlock, and a reduction in the distal arterial blood supply due to atherosclerosis was thought to result in ischemia of the navicular bone

Abnormal forces on the navicular bone could arise from either excessive physiological loads applied to a foot with normal conformation or normal loads applied to a foot with abnormal conformation.

Poor hoof conformation and balance, particularly the long toe, low heel hoof conformation accompanied by the broken-back hoof pastern axis, have historically been considered major risk factors for the development of navicular disease.

Clinical Findings and Diagnosis

Horses with navicular disease or syndrome usually have a history of progressive, chronic, unilateral or bilateral forelimb lameness, which may have an insidious (most common) or acute onset. The history may include a gradual loss of performance, stiffness, shortening of the stride, loss of action, unwillingness to turn, and increased lameness when worked on hard surfaces.

The disease is usually insidious in onset. An intermittent lameness is manifest early in the course of the disease. Because disease is bilateral, there may be no obvious head nod to the lameness when the horse is trotted in a straight line, with only a shortened stride present. Lameness is usually exacerbated by lungeing the horse in a circle in both directions, with the inside foot usually exhibiting the greatest lameness. In early stages of the disease, the lameness may not be visible even at a lunge until a nerve block is performed on one of the two digits (ie, the two lame feet cancel each other out). A flexion test of the distal forelimb may produce a transient exacerbation of lameness.

Clinical diagnosis is mainly based on presentation of the horse (age, breed commonly at risk) and, importantly, on the lameness examination, including a characteristic response to palmar digital nerve anesthesia. These horses are rarely positive to hoof testers (11% positive in one study). The lameness can be eliminated by palmar digital nerve block, except in some horses with extensive secondary moderate to severe damage to the deep digital flexor tendon (pain can radiate proximal to the palmer digital nerve block with this pathology). However, because this nerve block anesthetizes the entire sole and coffin joint in addition to the heel, response to the block itself is not diagnostic. A transfer of lameness to the other forelimb, which also is eliminated by a palmar digital nerve block, is necessary for a tentative diagnosis of navicular disease. Anesthesia of the navicular bursa is much more specific but is not as commonly performed during a lameness examination because of the pain involved in performing the injection (needle passes through the deep digital flexor tendon) and the complexity of the injection (usually done under radiographic guidance). Radiographic changes are variable and do not always correlate with the severity of lameness. Thus, they may not be as important in the diagnosis as the lameness examination (although they can be).

Radiographs may demonstrate a range of degenerative changes involving the navicular bone: marginal enthesiophytes, enlarged synovial fossae (so-called vascular channels) of variable size and cysts due to loss of medullary trabecular bone, general sclerosis of the medullary cavity, and flexor surface changes (observed on “skyline” radiographic view), including erosions and loss of a defined cortex.

Treatment

Because the condition is both chronic and degenerative, it can be managed in some horses but not cured.

The most common effective treatments include NSAID administration and corrective shoeing. Phenylbutazone is the most commonly used NSAID, but it must be used with caution because of adverse effects (renal and GI injury). If used daily, it may be best to take the horse off the drug one day a week to allow the body to clear some of the accumulated drug; the horse can be given flunixin for that day. Another option in horses at increased risk of NSAID complications is the COX-2-selective NSAID firocoxib, which is fairly effective for orthopedic and articular pain. With severe lameness, rest is indicated.

Foot care should include trimming and shoeing that restores normal phalangeal alignment and balance; response to corrective shoeing commonly takes ~2 wk. The principal object of shoeing is to decrease the pressure on the navicular bone. The shoeing technique that most effectively decreases pressure on the navicular area is raising the heel (usually performed with wedge pads or a wedged shoe). Rolling the toe of the shoe further relieves the pressure on the navicular bone. The egg bar shoe does not decrease navicular pressure in sound horses on a hard surface but has been reported to effectively decrease forces on the navicular bone in some horses with navicular disease or collapsed heels. Additionally, egg bar shoes are likely to more effectively decrease forces on the navicular area on soft surfaces (that horses are normally worked on); they are purported to work somewhat like a snowshoe by not allowing the heel to sink as deeply into a soft surface as a foot with a standard shoe would. Natural balance shoes are ineffective at decreasing navicular pressure.

Injection of the coffin joint with corticosteroids will markedly improve soundness in ~⅓ of horses (for an average of 2 mo), whereas injection of corticosteroid into the navicular bursa is reported to resolve the lameness for an average of 4 mo in 80% of horses that do not respond to standard treatments (phenylbutazone, shoeing, and coffin joint injection). Increased incidence of rupture of the deep digital flexor tendon has been reported with multiple intrabursal injections. Isoxsuprine hydrochloride is ineffective as a vasodilator when administered orally and has little therapeutic value.

Palmar digital neurectomy may provide pain relief and prolong the usefulness of the horse, but no neurectomy should be considered curative. Digital neurectomy has a high incidence of severe complications such as painful neuroma formation and rupture of the deep digital flexor tendon. Catastrophic injury to the distal limb in horses brought back to a high level of athletics after neurectomy has resulted in death of the rider. Other surgical procedures for navicular disease are unproved.

Although the prognosis is guarded to poor, a carefully designed therapeutic regimen, including corrective shoeing, NSAID therapy, and navicular bursa injections (and/or possibly coffin joint injections), can prolong the usefulness of most horses and the competitive status of many.