TABLE OF CONTENTS

Conformation of the horse

Conformation of the horse refers to the physical appearance and outline of a horse as dictated primarily by bone and muscle structures.

To develop an appreciation of lameness and gait defects, it is important to have an understanding of conformation and movement. While many lameness problems occur in the lower limbs, the causative factors may be located in the upper limbs or body; therefore, overall conformation should be considered. Certain conformation traits can predispose to lameness and these should be eliminated through responsible breeding.

Understanding the relationship between conformation, movement, and lameness is essential for making wise breeding decisions and devising sound management and training programs. However, breed conformational traits can differ and many conformational traits are not always related to performance and soundness. Furthermore, conformation is often a subjective assessment based on what a particular breed may consider to be “ideal.” Objective techniques to quantify conformation have been developed and are currently being used especially in Europe. Although a list of quantified conformational features of horses for sale or stallions at stud may be desirable, it seems unlikely to completely replace subjective conformational assessment and the art of selection.

Conformation

Conformation refers to the physical appearance and outline of a horse as dictated primarily by bone and muscle structures.

Conformation refers to how the horse is built, or the structural makeup of the horse.

Conformation affects how the horse will perform. For each particular purpose or function of horses, there is a particular form that will enhance that function. Consider the following points when evaluating the conformation and form of a horse for a certain function.

- The horse is an athlete. We must evaluate the structures which contribute to the horse’s ability to perform and remain sound.

- Conformation is inheritable – whether it is good or bad.

- Conformation plays an important role in the ability of a horse to perform.

- Conformation refers to the structure or outline of an animal as determined by the arrangement of its parts.

- Horses differ in conformation, which affects how well they can perform in different events.

- When choosing a horse, one should be able to recognize standard conformation and conformation faults and match the purpose of the horse with the conformation that is best suited for that purpose.

- Conformation is described as the physical appearance of an animal due to the arrangement of muscle, bone and other body tissue.

- To understand conformation, one must understand the framework of the horse.

- There is no perfectly conformed horse, however, each breed organization has their interpretation of an ideal horse. Prior to comparing two or more horses, it is essential to have a mental picture of the ideal horse for the breed.

- When judging or evaluating a horse, the first thing you should look for is overall balance. A horse that has balanced conformation will generally be a good mover, and that translates into good performance.

- The second thing you should evaluate is correct conformation. The structurally correct horse will be a natural athlete.

- Condition & muscling are the last things you should evaluate. Muscle mass and conditioning don’t change a horse’s basic structure, so less emphasis should be placed on it.

Conformation analysis and evaluation

Conformation analysis is the systematic comparison of one horse to another and all horses to an ideal type for the breed or athletic purpose.

Balance

Balance refers to the relationship between the forehand and hindquarters, between the limbs and the body, and between the right and the left sides of the body. It is a subjective assessment based on the overall conformation of the horse. A well-balanced horse is thought to move more efficiently, thereby experiencing less stress on the musculoskeletal system.

The centre of gravity is a theoretical point in the horse’s body around which the mass of the horse is equally distributed. It is located at a point of intersection of a vertical line dropped from the highest point of the withers and a line from the point of the shoulder to the point of the buttock. The centre of gravity is usually just behind the xiphoid and two-thirds the distance down from the top line of the back.

How do you evaluate balance?

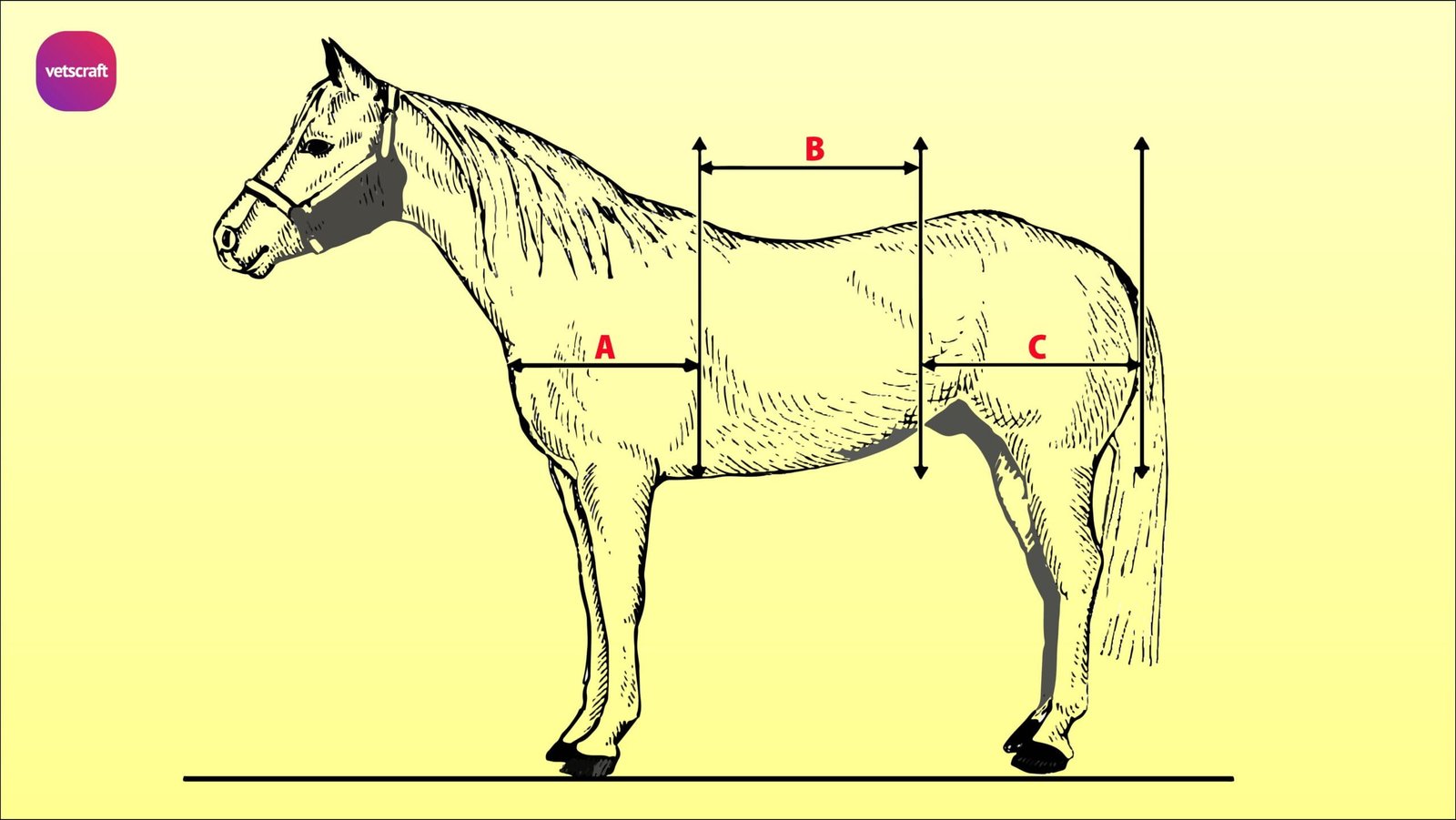

- First, evaluate the length of the horse by dividing the body of the horse equally into thirds.

- The horse should divide into three equal parts.

- The length of the neck should be as long as or slightly longer than the other thirds of the body.

- The length of the head of the horse should be approximately the same length as the neck or slightly shorter.

- Starting at the front of the horse, the first region is the shoulder (A).

- We define the length of the shoulder as the length from the point of the shoulder to an imaginary line that is perpendicular to the withers.

- The second region is the back (B).

- The length of the back is the distance from the base of the withers to the start of the croup.

- The third area is the hip (C).

- The length of the hip extends from the flank to the point of the hip.

- In a well-balanced horse, these three areas equal each other in length.

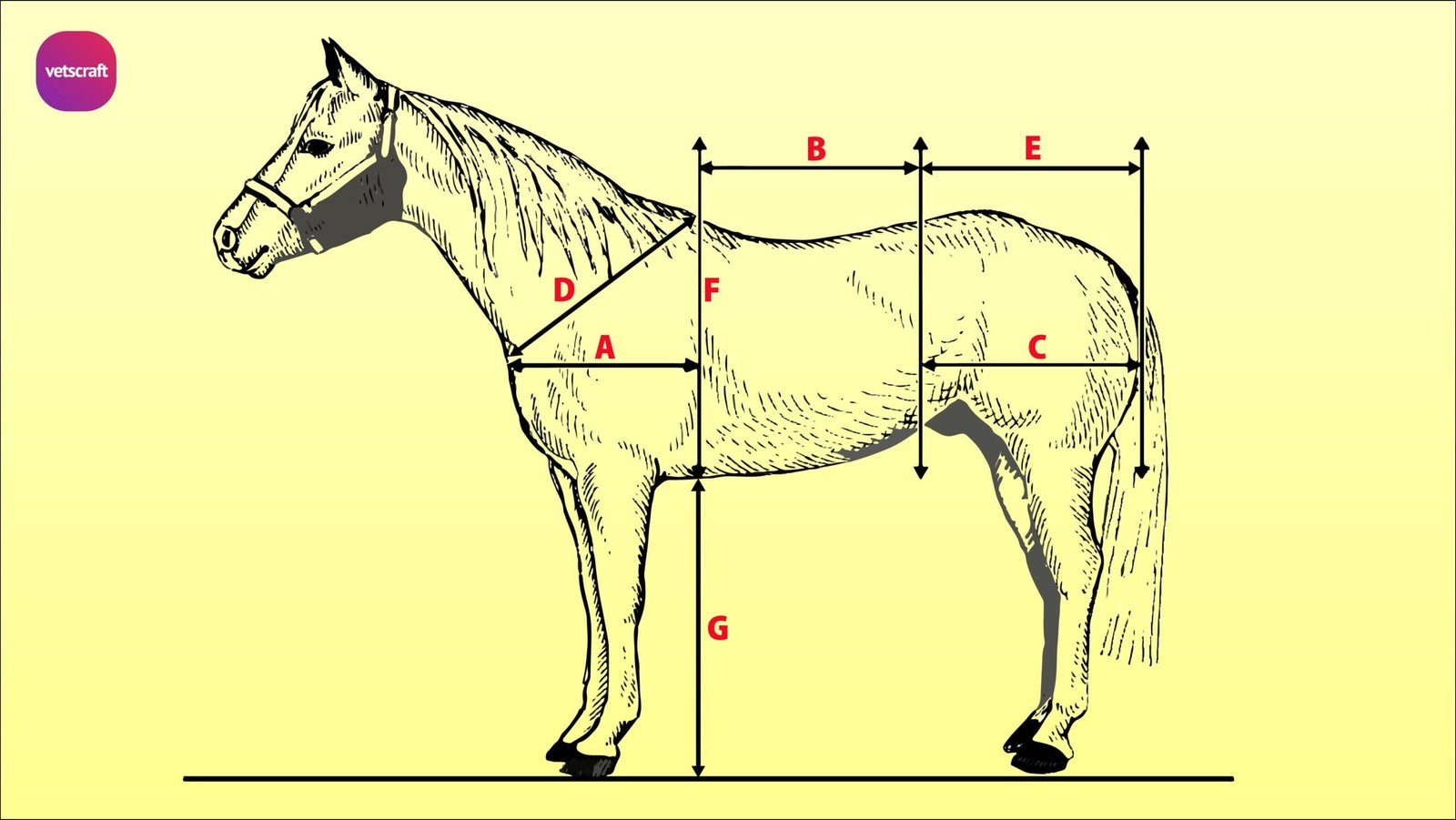

- Additionally, the horse should have a long, sloping shoulder (D); a short, strong back in relation to the underline of the body; and a long, comparatively level croup (E).

- Judges also look at balance from the withers to the ground, going from top to bottom.

- The measures dividing this line are called “depth of heart girth” and “length of leg.”

- Ideally, the distance from the withers to the girth (F), called heart girth, is approximately equal to the distance from the girth to the ground (G).

- A judge would like the horse to be level from the withers to the croup (known as the topline).

- Horses that are higher at the withers than at the croup are “uphill” horses, while those horses higher at the croup than at the withers are “downhill” horses.

- The withers of the horse should be the same or slightly higher than the croup of the horse. When the croup is higher than the withers, more weight is added to the front end. When a rider is added the problem is compounded.

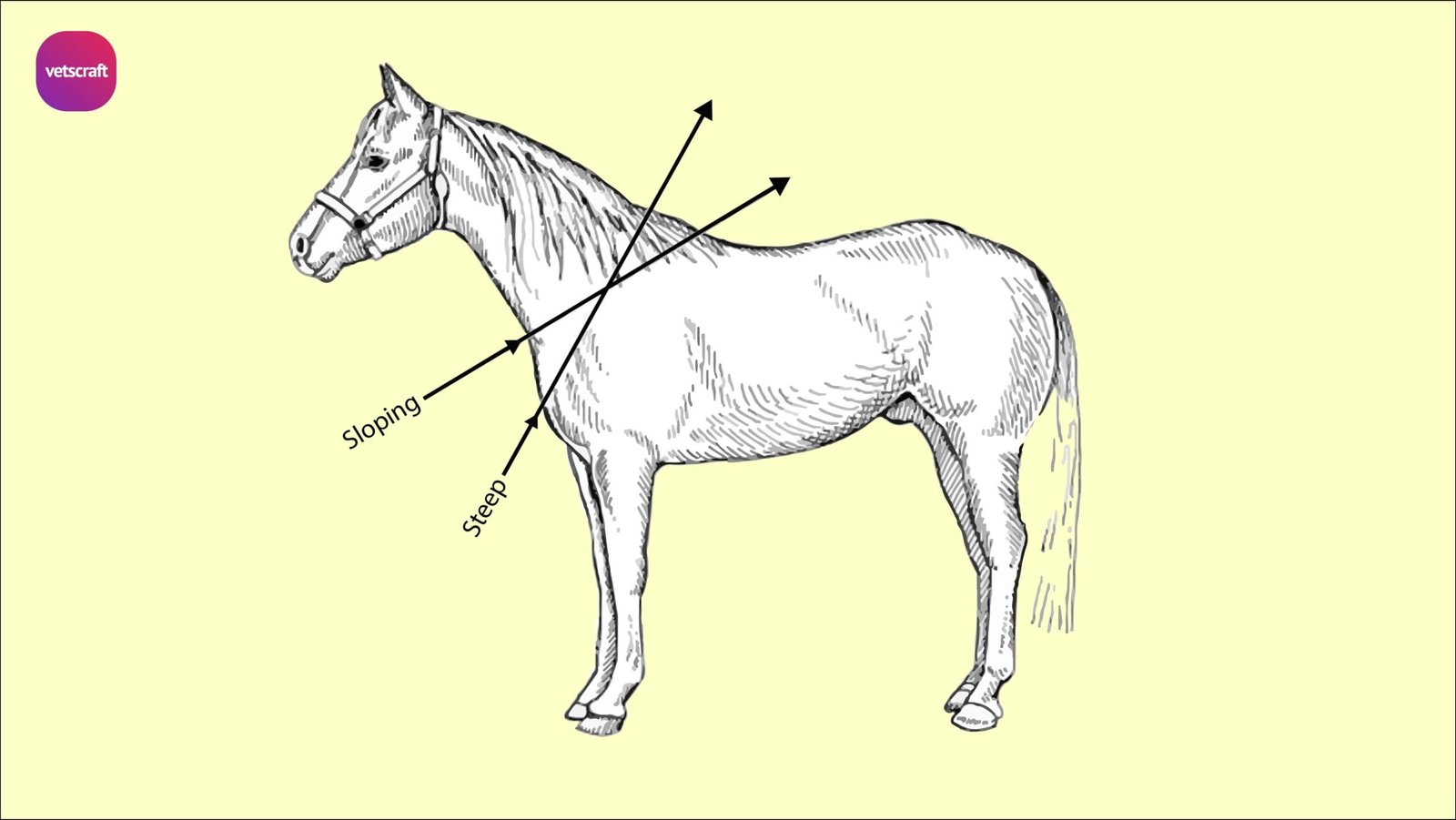

- Nothing is more critical to balance than the slope of the shoulder.

- A long, sloping shoulder is ideal.

- Look at the scapula to evaluate the shoulder.

- The slope, or angle, of a horse’s shoulder determines the length of its neck and back and also the way its front legs are set onto his body.

- As the shoulder becomes straighter, the withers move forward, which results in a longer back, and a shorter neck.

- When the shoulder is straight, the other angles of the horse’s body will be straight. Thus, the horse will have a short, steep croup, a straight stifle and straight pasterns.

- The ideal slope of the shoulder is approximately 45 to 50 degrees.

- In addition to overall balance, the slope of the shoulder influences length of stride. Thus, the straighter the shoulder, the shorter the stride.

- The angle of the shoulder and angle of the pastern serve to absorb shock when the horse moves.

- A straight-shouldered horse will always be a rough-riding horse.

- The longer the stride, the fewer the number of times the foot will hit the ground in a given distance, which results in less wear & tear on the horse and rider.

The depth of body from the withers to the bottom of the heart girth should be about the same as the distance from the heart girth to the ground.

Conformation

Conformation is essential for the judge to recognise structural defects. There are many structurally incorrect horses that are sound, but few unsound horses that are structurally correct.

Conformation is the biggest limiting factor to horse performance. There are a lot of things that can be done to improve the performance of a horse.

Performance can be improved through training, exercise & nutrition, health and even shoeing, but there is very little you can do about conformation especially in the mature horse.

- Conformation of head

- Conformation of Neck

- Conformation of the top line

- Conformation of the hindquarters

- Conformation of Barrel

- Conformation of the Legs

Conformation of head

- A large eye on the corner of the head with a wide flat forehead.

- A greater arc of vision.

- During it’s evolution, the eye has moved from the front of the horse’s head to the side, which provided a more rounded arc of vision (about 300 degrees).

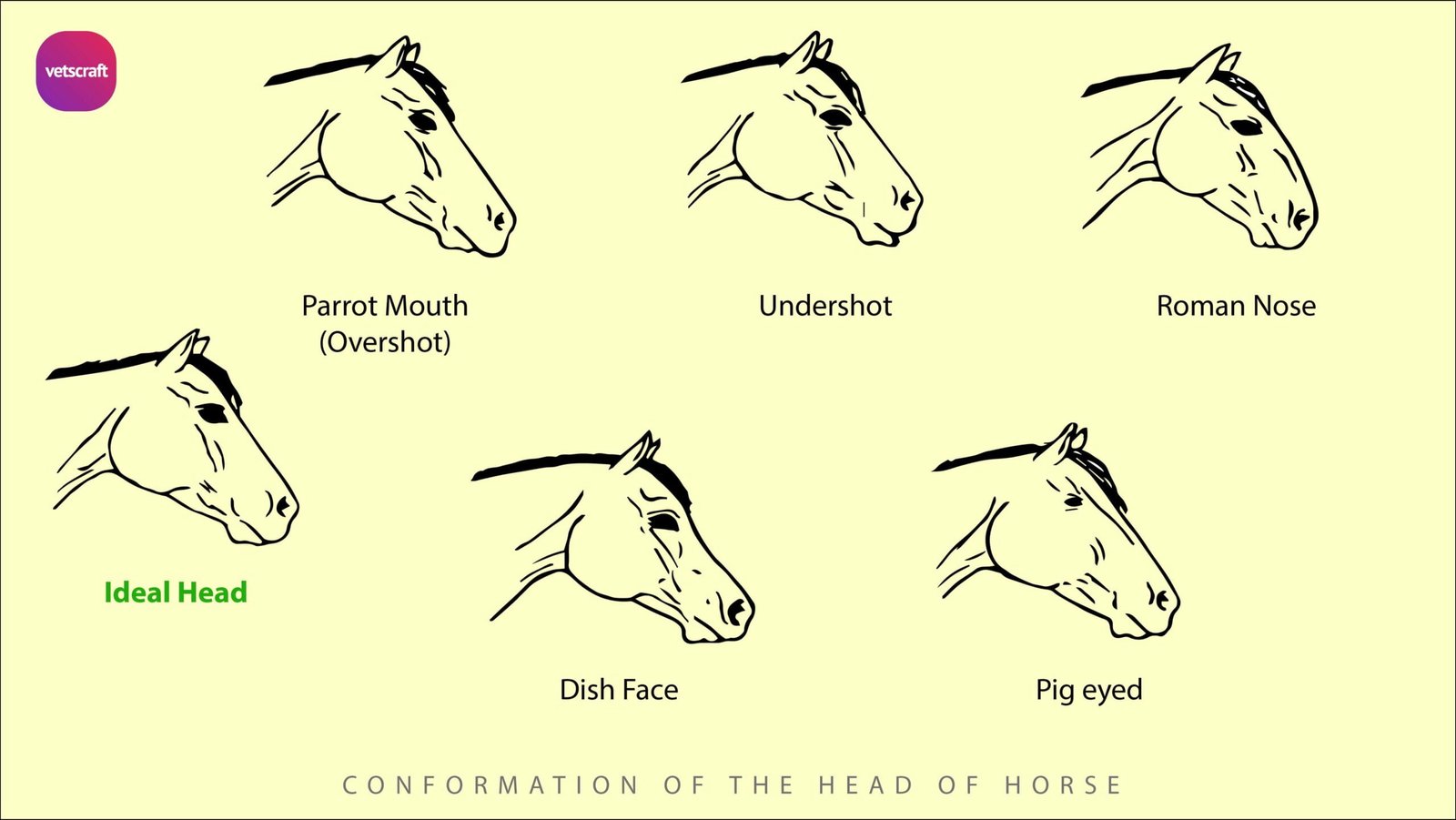

- Large, quiet, soft eyes often indicate a quiet, docile disposition. A small “pig-eye” is indicative of a horse that is somewhat sullen and difficult to train. A “pig-eyed” horse has a smaller eye socket positioned more on the side of the horse’s head then on the corner. These horses are notorious for a poor disposition.

- Some feel that a horse with excessive white around the eye is often nervous and flighty.

- Look for a bright, tranquil eye that has a soft, kind expression.

- The ears should be proportional to the horse’s head, sit squarely on top of the head, point slightly forward creating an attractive, alert appearance.

- When measuring a horse from the poll to a horizontal line drawn between the eyes, the distance should be approximately one-half the distance from the horizontal line to the midpoint of the nostril. Thus, the eyes will be positioned one-third the distance from the horse’s poll to the muzzle. When the width of the horse’s head across the orbit of the skull is measured, the distance should be almost identical to the distance from the poll to the horizontal line drawn between the eyes.

- Horses are not capable of breathing through their mouths, so the size and shape of the nostrils are important to horses in highly aerobic activities, such as racing.

- This is the reason that Thoroughbreds tend to have larger nostrils, with finer cartilage and a large, flaring nostril to facilitate adequate air intake.

- Sufficient length between the nostrils and the eyes is important to allow the tubinates located there to heat or cool the air to near body temperature.

- Roman-nosed refers to a horse with a convex profile such as is found in the draft breeds, as opposed to the concave, or dished, profile of the Arabian and similar breeds.

- A roman nose on a horse can also obstruct the field of view of the horse.

- Too large of a head adds weight to the end of the neck, which serves as the horse’s balancing arm, effecting his agility.

- Look for a well-defined jaw. Stallions will have a slightly larger, deeper jaw than mares, indicative of common male sex characteristics.

- Depth of mouth is influences the response and sensitivity experienced by the horse during training. The more shallow the mouth, the more reactive the horse; the deeper the mouth, the less reactive.

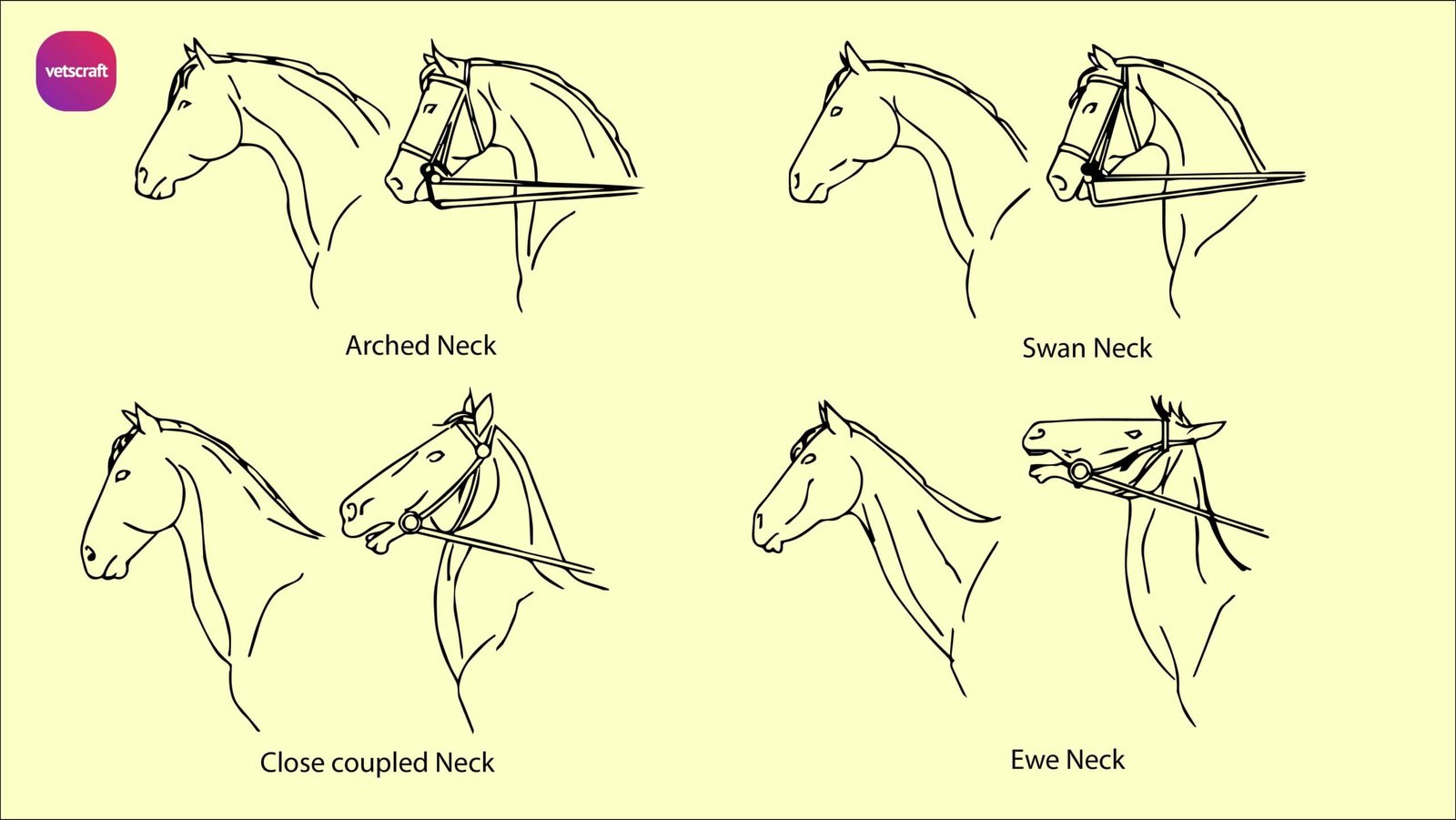

Conformation of Neck

- The head and neck are mechanisms for balance in a horse.

- An ideal neck is long and trim, with a clean throatlatch.

- The throatlatch should be trim and refined regardless of the breed.

- Air, food, blood to and from the brain, the entire nervous system and important glands behind the jaw must pass through the throatlatch.

- A horse that is thick and coarse in the throatlatch, will have difficulty carrying its head in a vertical position during training because of an inability to breathe correctly.

- A clean throatlatch means that enough space occurs between the jaw, throat, and neck, allowing the horse to move its head and neck without difficulty.

- A horse with a wasty (thick and fat) throatlatch may have difficulty breathing.

- The neck top line is the distance of the poll to the withers, and the bottom line is the distance of the throatlatch to the neck-shoulder junction at the chest. The ideal distance would be approximately a 2 to 1 ratio of the top to bottom line of the horse’s neck. Invariably, a horse that is short and heavily muscled will have a shorter, thicker neck than a taller horse with less muscle. The neck is proportional to the horse’s overall length and height.

- Stallions are more prone to have more crest along the topline of the neck than either geldings or mares.

- Some horses, such as the Quarter Horse, have a lower set-on neck than do others, such as the Saddlebred.

- This predisposes the Quarter Horse to carry its head lower, which is desired in Western Pleasure classes and makes it a natural choice for these classes.

- Many of the carriage breeds, such as the Cleveland Bay, the Friesian and some of the German Warmbloods have a much higher neck, giving them a higher head carriage which lends an air of presence.

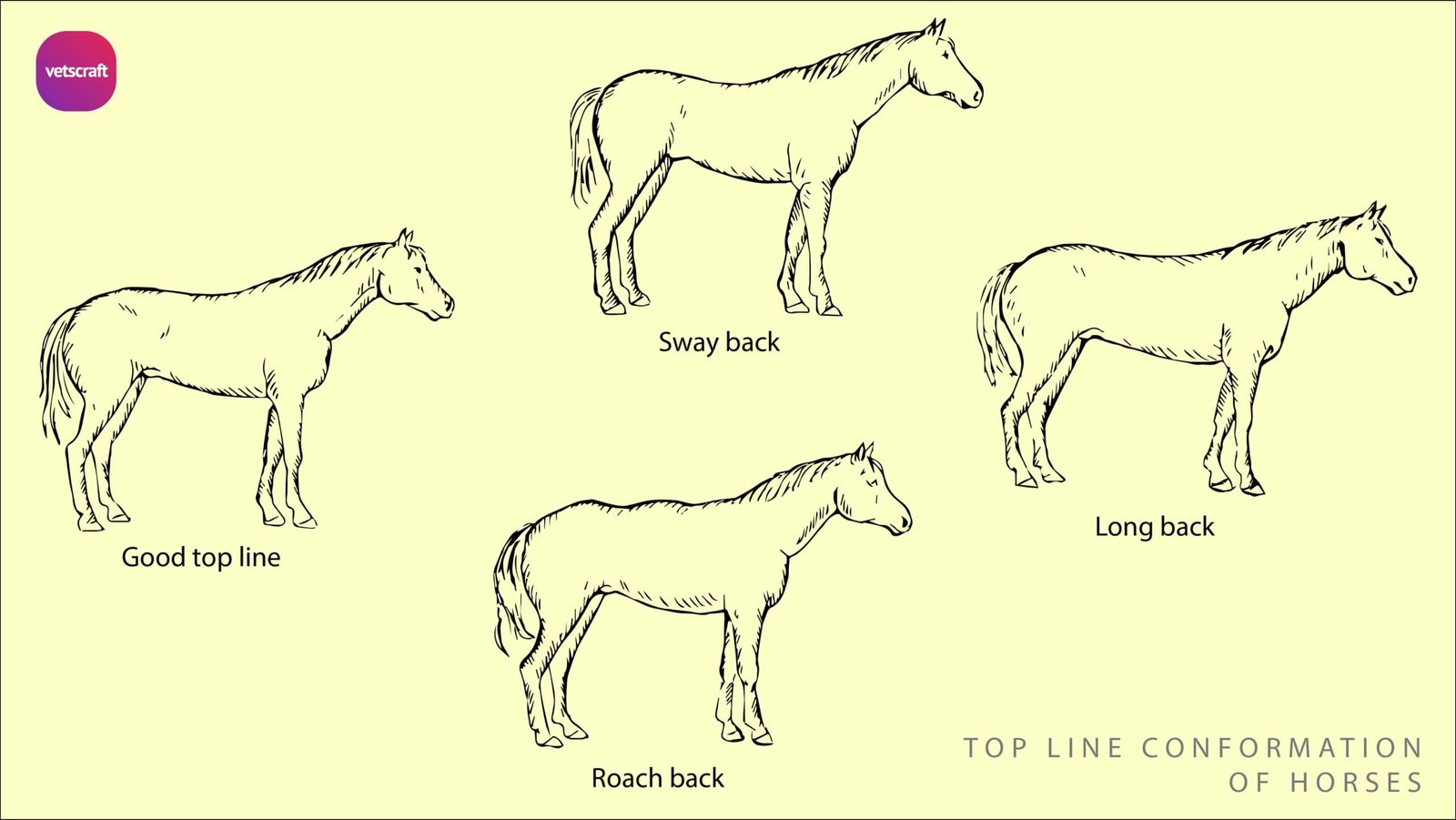

Conformation of the top line

- The back is a very important part of the riding horse. The horse is not naturally a weight carrier, it is more designed by nature to be a weight puller, so it is especially important to make note of types of conformation that predispose the horse to even greater weakness in the back.

- Horses with long backs are not well-balanced; the long back breaks up the smooth line of the top line.

- The back of a horse should have adequate muscling to be able to support the rider.

- The loin is only supported by the vertebral column; it should be short from front to rear, wide across, smooth, and convex, with a firm, elastic consistency.

- Without adequate muscling, a horse is inclined to become swayback (a back that sags).

- Too much length in the back can affect the gait, giving the hindquarters a rolling motion.

- The back is the “hub” of a horse, and a short, strong back is essential to a horse remaining sound and performing well.

- First of all, the back should be neither too long nor too short and should be shaped in a manner that accepts a saddle comfortably.

- A back that dips excessively is called a sway back and is generally found in older horses. Its opposite is called a roach back. Both can cause difficulties with fitting a saddle.

- A horse with a convex back, or “roach back,” may cause the lower legs to interfere.

- A roach back is often a sign of spinal misalignment and it lacks flexibility.

- A roach backed horse exhibits a short stride and tends to overreach.

Conformation of the hindquarters

A croup without too much angle is desirable; a steep croup can mean a weak hip and incorrect angulations to the horse’s hocks. A long, strong hip with adequate muscling and low hocks is desirable. These attributes generally result in a horse that can stop well and will naturally work off its hind end, making it a stronger athlete.

The hindquarters should appear square, when viewed from the side.

The ideal horse has a quarter that is as full and as long from across the horizontal plane of the stifle as it is from the point of the hip to the point of the buttocks.

- Horses should have long hips in relation to other areas of their bodies.

- The hindquarters contain the driving force of the horse’s locomotion.

- Muscling is evaluated by looking at the length and definition of the muscle that passes over the croup.

- The horse should also have well- developed stifle muscles that extend down toward the hock.

- Croup length affects stride length

- Horses with short croups have short, uneven strides

- Horses with long croups have long, flowing strides

Conformation of Barrel

- Evaluate the spring of rib and depth of the heart girth, as these are indicative of lung capacity.

- The shape and size of the chest controls the amount of room the lungs have to expand, which is important in the athletic horse.

- A horse with a chest that is too narrow not only will have its aerobic capacity reduced, but its forelegs will also be too close together, making it more likely to brush his forelegs together when being worked, possibly causing injury.

- The body should be rounded and the ribs well-sprung.

- Ideally, a horse should be deep in the heart girth and have large circumference of the heart girth.

- This allows the horse to have enough space to hold the vital organs, which improves the horse’s performance.

Conformation of the Legs

- Skeletal structure controls conformation; the feet and legs are crucial parts of conformation

- It has been said that the legs are the most important part of the horse, for if a horse has weakness or bad conformation in its legs, its athletic ability is going to be seriously compromised, regardless of how it will be used.

- Performance horses are athletes; they must have straight legs.

- Straightness of legs refers to the alignment of the column of bones in the front and rear legs.

- The forearm should be long and muscular with a shorter cannon bone.

- The knee should be large and flat, not round and puffy. The tendons have to pass through the knee to the lower leg and that is why large, flat knees are desirable to allow the maximum movement.

- Knees and hocks should be close to the ground for the horse to cover ground quickly and easily

- The lower leg, when viewed from the side, should have a flat appearance. A flat appearing lower leg means the horse has a big bone and the tendons and ligaments to fit it.

FRONT FEET AND LEGS

- The horse should stand on a straight column of bone with the line of concussion going straight down the forearm, through the knee, down the cannon bone and coming out at the heel of the hoof.

- The front legs bear 60 – 65% of the weight of the horse. If badly conformed they are much more prone to damage when subjected to stress, strain and concussion.

- The arm (humerus) should be short in comparison to the length of the shoulder.

- An arm that is too long places the foreleg way too far under the body and the horse will carry too much weight on the front part of its body.

- An arm that is too short cuts the horse’s stride length.

- The forearm should be long and have muscles that attach deep into the knee.

- This will promote a long stride, especially if the horse has a comparatively short cannon bone.

- A horse that is “over at the knees” is buck-kneed, and the horse that is “back at the knees” is calf-kneed.

- Obviously, calf-kneed is the most serious condition since the knee will have a tendency to hyper-extend, or bend backward.

- When the horse is viewed from the front, an imaginary line from the point of the shoulder to the toe should bisect the knee, cannon bone and hoof.

- The cannon bones should be short (compared to the forearm).

- This will allow the knees and hocks to remain closer to the ground, which will increase stability and create a longer stride.

- The cannon bones should be refined (see tendons clearly articulated) and have a “clean appearance.”

- The cannon bone is round; but, it should appear flat, when viewed from the side, due to the tendons behind it.

- Rear cannon bones can be larger than the front cannon bones.

- The horse hoof should point straight ahead. When a horse toes out, it is splay-footed and the horse will always wing in when it travels.

- When a horse toes in, it is pigeon-toed and that horse will always paddle out.

- The most serious of these is the horse that wings in because it has a tendency to strike its legs with the opposite hoof as it travels.

- If the cannon bone is off-centered to the outside, it is bench-kneed.

- The pastern is the horse’s shock absorber, at times carrying the horse’s entire weight plus that of the rider.

- The pasterns should be moderately long and sloping.

- The ideal pastern is neither too long nor too short, too sloped or too upright. Overly long sloping pasterns will place a strain on the suspensory ligament and the tendons which run down the back of the leg. Pasterns which are too upright do not flex sufficiently to overcome the strain of movement, consequently, the leg may experience soundness problems because of it.

- A horse that has too much slope to its pastern is also undesirable and is said to be coon-footed. This condition can become so severe that the horse’s fetlocks hit the ground as the horse moves.

- The angle of the hoof and the pastern should be the same.

HOOF

- There is an old saying, “No hoof, no horse”.

- The hoof should be of sufficient size and shape to support the mass of the horse and absorb concussion.

- Hoof walls should be free of major cracks where the outer wall is actually split from the coronet down. Such cracks may cause a horse to be lame.

- Hooves should be clear of founder rings.

- Front feet tend to be round. Hind feet tend to be more pointed. Both front feet should be the same shape and size, and both back feet should be the same shape and size.

HIND FEET AND LEGS

- Like the knee, it is preferable for the hock to be set low, thus lessening the strain on the hind cannon.

When standing beside the horse, the judge drops an imaginary line from the point of the buttocks to the ground. Ideally, that line should touch the hocks, run parallel to the cannon bone and be slightly behind the heel. The horse with too much angle to his hocks is sickle-hocked, and the horse that is straight in his hocks is post-legged.

Ideally, when viewed from the rear, any horse, regardless of breed, should be widest from stifle to stifle. Another imaginary line from the point of the buttocks to the ground should bisect the gaskin, hock and hoof.

When a horse is bowed-in at the hocks and the cannon bones are not parallel, it is cow-hocked. The horse that is cow-hocked has a tendency to be weak in the major movements that require work off of the haunches such as stopping, turning, sliding etc. There are horses that actually toe-in behind and are bow-legged, most of which are very poor athletes.

Conditioning

Generally, Horses don’t break down due to weak muscling. With proper training muscle mass and conditioning can be improved. A correct horse that lacks muscling should always be placed higher than a structurally incorrect horse that is well muscled.

Muscling

- Muscling is an important criteria in judging many conformation classes, especially stock horse classes, such as Appaloosa, Quarter Horse and Paint Horse.

- The ideal horse is a balanced athlete that is muscled uniformly throughout. Horses which are visually appraised as heavily-muscled generally have greater circumference of forearm, gaskin and width of quarter than lightly muscled horses.

- As viewed from the front, the horse should show significant width from shoulder to shoulder, a large circumference to the forearm, and a prominent “v” in the front muscling.

- When viewed from the side, a horse should have strong forearms, a deep quarter, strong gaskins, and a long croup to accommodate a large amount of muscle mass through a prominent stifle. In addition, the horse should have a large-circumference heart girth.

- Muscle in the front shoulder is especially important because it is the primary means of attachment to the body. There is no clavicle in the horse.

- As viewed from the back, the horse should be wide from stifle to stifle, and the quarter should tie in deep to strong gaskins.

MUSCLE EVALUATION

- Forearms – powerful muscles that tie deeply into the knee;

- Sufficient width between the front legs;

- Chest muscles (pectoral) need to have bulge and quality – long and deep tying;

- Back and loin muscling is imperative to support the rider’s weight;

- Coupling (connection of loin with hindquarters) should be intensely muscled and wide to help support the loin; it should also be short and strong;

- The hindquarters are the source of power for the horse; they should be broad and well-muscled.

- Different breeds of horses exhibit various degrees of muscling.

- The degree of muscling is also correlated with the events in which the horses compete.

- Horses used for events that require power (pulling, working cattle, reining) should have larger, bulkier muscles.

- Horses used for speed events (sprinting, barrel racing, middle and long distance racing, eventing, and jumping) should have long, slim muscles.

- Width through the stifle and width through the hips indicate how heavily muscled a horse is through the hindquarters.

- A more heavily muscled horse is wider at the stifle than at the hip.

- Thigh muscles should be powerful, wide, and deep.

- Stifle muscles should be long, extending into the gaskin.

- The gaskin muscles should be bulky and should be apparent on both the inside and outside of the gaskin.

When judging horses, take all factors into consideration. the best individual horse will be the one that has balance, structural correctness, muscling, travel, and quality.